Custody

Divorce by itself is heart-wrenching, and the addition of children to the equation makes it even more challenging. If a couple doesn’t have children, and they insist on dragging their divorce into court and litigating away much of their savings, at least the victims of the damage they inflict are adults. Sadly, when minor children are involved, the emotional harm resulting from a high conflict divorce may last for many years. Indeed, many now-middle-aged individuals who endured a high conflict divorce when they were children still consider it the most painful and scarring experience of their lives.

Sound intimidating? Take heart in the fact that millions of divorced parents have navigated their way through the process while making their children’s emotional welfare their top priority. This is well-traveled territory, and with some careful planning, good intentions, and a strong heart, you can not only survive the process, but you can also ensure that your children are raised in a stable, loving environment. When sorting out custody, the key to success involves that same tired refrain—act like a grownup. Your children need you to behave—desperately. If you can’t compose yourself and act with dignity for your own sake, do it for theirs.

If the negotiation process breaks down and you and your spouse simply can’t agree on who should care for your children, you will undoubtedly wind up in court. As noted elsewhere in this book, family court judges are exceedingly busy. While resolving custody disputes is a very important part of their job, judges simply don’t have the time or the insight into the details of your children’s lives to make a “perfect” decision, if such a thing exists. You can take heart in the fact that judges really do their best to look out for the interests of your children, but you can also be sure you will achieve a better result by using a mediator to resolve custodial conflict.

If you simply can’t resolve the issue of how responsibility for taking care of the children should be shared, you should skip ahead to the section titled “The Legal Framework for Custody.” There you will find a description of how a judge and/or a court-appointed custody evaluator will decide who should care for your children. Before you throw in the towel, though, please do everything in your power to work with your spouse to resolve your issues. It’s better for your children, and it’s better for you.

Here are a few basic things you need to know about child custody:

- If a couple can’t reach agreement on custody, a mental health professional known as a custody evaluator, not a judge, typically decides how custody will be shared.

- Before a judge makes anything more than a temporary award of custody or visitation, California law requires spouses to mediate their differences.

- Most judges would consider a child’s degree of attachment to each parent the most important factor in evaluating custodial arrangements.

- The law governing whether a custodial parent may relocate children out of state has changed repeatedly, and it is now almost impossible for a noncustodial parent to prevent relocation.

Custody, Practically Speaking

Understand the Basics– Legal Custody vs. Physical Custody

The term physical custody refers to the parent (or both parents, if custody is shared) who has physical responsibility for the care of the children. The term legal custody refers to the parent (or both parents, if custody is shared) who will possess decision-making authority relating to the health, education, and welfare of a child.

The term joint physical custody is often misused in California. It does not mean equal time-sharing, as many seem to believe. Indeed, a parent who only sees his or her children every other weekend and a few weeks during the summer may be awarded joint physical custody. This has the benefit of avoiding the term “visitation.” No parent wants to feel like a visitor when spending time with his or her own children. The term sole physical custody simply means that one parent has the right to have the children live with him or her.

Although the term primary physical custody is not defined anywhere in the Family Code, family courts continue to use the term. This can have a significant impact when one spouse wants to relocate the children. If that spouse has sole physical custody or even primary physical custody, he or she may be permitted to leave with the kids without the permission of the other spouse (see “Moving Children Away” below). When dealing with percentages, a spouse who has custody of the children less than 45% of the time may be in danger of helplessly watching them leave.

Joint legal custody means that both parents have the authority to make decisions regarding the health, education, and welfare of the children. This involves determining whether or not they should attend church, where they should attend school, and when they should be able to obtain a driver’s license. Sole legal custody means that one parent has the authority to make all of these decisions.

How You Can Help Your Children

If you haven’t yet achieved a sense of peace regarding the fact that you are headed for divorce, you may struggle to project the sense of strength and calm that your children crave. Indeed, you may be struggling through the first stage of divorce for many individuals: denial. Pretending nothing is wrong and refusing to acknowledge where things are headed will not benefit your children. Unless they are very young (i.e., less than three years old), chances are they are acutely aware of the tension between you and your spouse, and they may know that divorce is likely. Don’t shield your children from the truth, but do insulate them from your “adult” problems. They don’t need to know that your spouse slept with a coworker, or that he or she wants to financially destroy you. They do need to know that you love them, unconditionally, and that while you are beginning the painful divorce process, none of this is their fault.

Also, as you begin negotiating custody arrangements with your spouse, try your hardest to turn off the calculator in your head that starts equating increased custody with lower child support payments, or vice versa. Undoubtedly you love your children, and try to remember that creating a good custody plan requires you to put their interests first. Some financially savvy spouses (particularly breadwinners in one-income families) will fight for increased custody so that their support payments decrease. In the end, this game always backfires. The parent who fought so hard for a higher percentage of physical custody in the interest of reducing child support often finds that the reality of caring for the children is overwhelming.

The most painful reality of all when it comes to custody is that some parents simply shouldn’t push for more time with the children. We have been programmed to believe that we should do everything perfectly: be the perfect employee, the perfect friend, the perfect parent. A palpable sense of shame often accompanies the admission that caring for the children every other week is simply too much.

Honest introspection will always serve you well. Look deeply inside yourself and ask whether you truly have the capacity to care for your children half of the time. If your spouse is floundering, you may not have a choice (indeed, you may end up with sole physical custody). In that case, you should reach out for parenting support from as many sources as possible. But if your spouse is a stellar parent, and you feel overwhelmed with the task of caring for your children half of the time, you need to consider alternate custodial arrangements. Admitting that your spouse may be better suited to the critical task of child rearing is not an admission of defeat, though it may feel like one. It’s simply being realistic, and honestly assessing your own skill set is a powerful first step in establishing a suitable custodial arrangement.

Developing a Parenting Plan– Core Issues

Where will the children live?

Deciding where your children will live after your divorce is perhaps the most critical decision you will make during the settlement process. This decision not only involves the basic question of whether they will live in one residence or split their time between two homes, but naturally also involves how much time they will spend with each parent. There are several possible approaches with regard to housing your children, and they include (a) one home, (b) dual homes, (c) someone else’s home, and (d) one home on a time-share basis.

One Home

For many children, picking one home as the primary residence makes good sense. Young children in particular may thrive on the routine and familiarity associated with a single home. Having one bedroom, one set of clothes, one chest full of toys, and one set of neighborhood playmates may add stability to their lives. Of course, having one primary home has disadvantages as well. The importance of the relationship between the noncustodial parent and the children may be diminished over time. In addition, the children may feel like visitors when they travel to the noncustodial parent’s home for the weekend.

Another potential challenge of having the children primarily reside in one home is that the noncustodial parent may start to fall into the role of the “fun” parent. While the custodial parent is saddled with the unglamorous tasks associated with day-to-day living (changing diapers, shuttling kids to soccer practice and music lessons, doling out discipline, etc.), the noncustodial parent focuses solely on having a good time with the kids. This can arise from the noncustodial parent’s overpowering desire to have the children like him or her despite the limited interaction between them. It can also arise from the noncustodial parent’s desire to cram as much activity into one weekend as possible (making up for lost time). Sadly, it can also result from laziness. Disciplining kids and shaping them into responsible human beings takes a lot of love and a lot of work. Caving in is easier, particularly when the noncustodial parent assumes the other parent is taking care of the essentials.

The custodial parent may begin to resent the fact that the kids return home from their “fun weekend” with tales of adventure, staying up late, watching movies, and jumping on the bed. It may take a few days for the children to settle back into their normal routine. A responsible noncustodial parent will be conscious of the responsibility associated with his or her role. Fun is important—true. But so is being a real parent who contributes in meaningful ways to the children’s development.

Custodial arrangements involving one primary home can take on a number of forms. A few of the more common arrangements are as follows:

- Alternating weekends (Friday night to Saturday night). For parents who live in reasonably close proximity to one another, this custody arrangement is often viewed as the minimal amount of time the noncustodial parent should spend with the children. Four overnights in a one-month period is not a lot, and the children may feel themselves drifting away from the noncustodial parent. This arrangement also has the disadvantage of allowing the custodial parent very limited (if any) involvement in school and extracurricular activities. Lastly, the custodial parent doesn’t get much of a break from the relentless task of raising the children.

- Modified alternating weekends (Friday night to Monday morning). This schedule has the advantage of allowing the noncustodial parent to drop the children off at school on Monday, as well as providing another night with the kids. Of particular importance in bitter divorces, it also presents less opportunity for conflict, as the custodial parent need not interact with the other parent when dropping the children off at school on Monday. If the noncustodial parent has some flexibility with regard to his or her work schedule, the transitions can become even smoother if the children are picked up directly from school on Friday.

- Alternating weekends with a mid-week overnight. (Friday night to Monday morning, and Wednesday night to Thursday morning). This clearly has the advantage of allowing the noncustodial parent more time with the children, but the schedule can be highly disruptive. Children in school are forced to consider whether it is Dad’s night or Mom’s night, and whether they have what they need at each residence. This type of arrangement can result in frequent trips back and forth between both parents’ homes. (As in, “Mom, I forgot my math textbook at Dad’s, and I have a test tomorrow.” Or, “I accidentally brought the wrong clothes for school tomorrow. I need to go home and get something else.”) While this schedule can work, it takes resilience on the part of the kids, who may never quite feel settled.

- Alternating weekends, alternating or split holiday vacations, and part of the summer. This option has the distinct advantage of allowing the noncustodial parent to spend extended amounts of time with the children when school is not in session. For instance, if the noncustodial parent can get the time off, arrange for day camp, daycare, or hire a part-time nanny, the children can spend several weeks in the summertime living with the noncustodial parent. Winter break can either be split (one week with each parent) or the children can alternate the time off (winter break with one parent one year, and the other parent the next year).

Of course, when the children are infants or toddlers, overnights at the noncustodial spouse’s residence may not be appropriate. This is particularly true when the noncustodial parent never had sufficient time to bond with the children before the divorce. In these situations, the noncustodial parent may be stuck with short visits, at least until the children are older. There are many possibilities involving short visits. Here is one:

- Three weekly visits of several hours each. For exceptionally young children, being away from the parent with whom they are bonded can be quite uncomfortable. Limiting visits to a few hours at a time, at least initially, is a safe bet. For conflict-free parents, these visits can take place in the custodial parent’s home, where the child will enjoy the security of familiar surroundings. For all others, either the noncustodial parent’s home or a neutral location like a park (weather permitting) may be best. When the child becomes used to spending time alone with noncustodial parent, longer visits and overnights can be added.

Two Homes

Many divorcing spouses choose to have their children spend equal amounts of time with each parent. In this sense, the children truly do have two homes. This can be logistically or financially challenging, as the children will either need to cart their clothes and favorite belongings back and forth between two homes, or the children will need two sets of everything. In addition, parents who wish to share custody fairly equally and maintain two fully functional homes for their children must acknowledge that their children may frequently interact with the other parent’s new partner. A few of the more common arrangements when the children live in two household are as follows:

- One week on, one week off. This has become a very common arrangement between spouses who live close together and both work. It has the obvious advantage of granting each parent equal time with the children, and the commensurate benefit of giving the children an equal chance to bond with both parents. This arrangement works particularly well when the parents are civil and can work together to raise the children with only minimal friction. In some situations the parents live close enough to one another that the children can walk or bike between houses. Many mental health professionals suggest that this schedule is most suitable for tweens and teens, as it involves spending seven days away from each parent.

- One week on, one week off, with midweek dinner visit. This schedule has the advantage of reducing the amount of time the child is away from each parent by including a weeknight dinner with the “off” parent. This often works well for young children who are uncomfortable being away from one or both parents for more than a few days at a time.

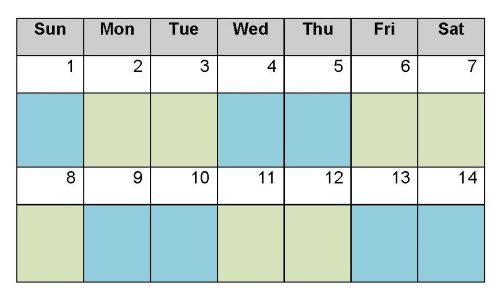

- 2-2-3. This is an equal-time-sharing arrangement that merits a bit of explanation. Under this scenario, a two-week schedule is maintained. During Week 1, one parent has custody of the children from Monday morning to Wednesday morning, and again from Friday morning to Monday morning of Week 2. During Week 2, that same parent has custody of the children from Wednesday morning to Friday morning. In other words, Monday and Tuesday always go together, Wednesday and Thursday always go together, and the three-day weekend (Friday through Monday morning) always goes together. By rotating who takes custody of the children during each of these periods each week, the maximum amount of time that either parent will spend away from the children is the three-day weekend (hence the “3” in the 2-2-3). Here is a simple visual (Parent 1 is blue, Parent 2 is green):

The advantage of the 2-2-3 is simply that it limits time away from the children. The disadvantage is also clear – rotating weekdays as set forth above creates an additional transition and requires calendaring.

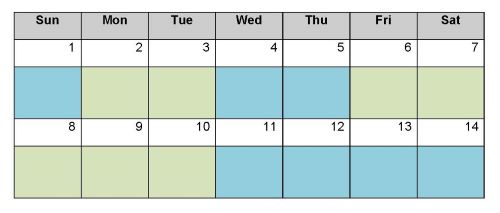

- 5-5-2-2. A 5-5-2-2 is similar to a 2-2-3 in many respects. However, instead of alternating who takes custody of the children from Monday morning to Wednesday morning and from Wednesday morning to Friday morning, the Monday through Thursday schedule remains constant. In other words, one parent always has custody of the children on Monday and Tuesday, and the other parent always has custody of the children on Wednesday and Thursday. Three-day weekends are alternated in the same manner as the 2-2-3. Again, here is a simple visual (Parent 1 is blue, Parent 2 is green):

The advantage of the 5-5-2-2 is that the maximum amount of time either parent spends away from the children is five days (as opposed to seven with a “one week on, one week off” schedule). Another advantage of the 5-5-2-2 is that the Monday through Thursday schedule is consistent, which simply means that there are fewer transitions than with a 2-2-3.

- Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday (all day) and Wednesday (morning) with one parent. This is a compressed equal-time-sharing schedule, which has the advantage of decreasing the time between homes. However, this schedule has a significant disadvantage, which involves the increased chaos of moving every three and a half days. This also has the disadvantage of saddling one parent with the “less fun” beginning of the week, while the other parent gets to share the excitement of the weekend with the children.

- Weekdays with one parent, weekends with another. This presents a degree of stability and predictability that is nice, but the parent with weekday parenting duties may miss having time with the children while they are out of school. Furthermore, the parent who has the kids every weekend may long for a break.

- Weekdays with one parent, weekends with another (modified in summer). This modified schedule reverses itself in the summertime, so that the parent who has the children during the week during the school year has the children every weekend during the summer. This can provide a nice change of pace for both the parents and the children.

One Home Shared by Both Parents (Often Known as “Nesting”)

This is a rather unconventional custody arrangement, but it can work in certain circumstances. If the parents get along beautifully, the house can be shared. While one parent is living with the children, the other lives in an apartment or makes other housing arrangements. The children enjoy the benefit that comes from the stability of having one home, but the parents may have a hard time effectively living in two residences. The complication of continuing to share space with a former spouse also makes this a tricky arrangement. In short, while parents who nest often do so for the best reason of all (i.e., doing so minimizes disruptions in the children’s lives), it comes with a host of challenges that typically make it a transitory arrangement.

Commuter Parents

Although it is always unfortunate, life circumstances sometimes require one parent to live in an entirely different state, or even on the opposite side of the country. For these noncustodial parents, flying out to see their children may be the only viable option when it comes to regular visits. Crossing the country every weekend is rarely an option, as the schedule will quickly wear the non-custodial parent down so much that it impacts his or her ability to function properly as a parent. For some truly hardy souls (who also can afford the significant expense of crossing the country so frequently), flying out to see the children every other weekend is a possibility. Again, depending on their work schedule, many parents find this arrangement is simply untenable.

At a minimum, a parent who lives on the opposite coast would be well advised to try to make the trip to the custodial parent’s home at least once a month. If the relationship between the parents is anything but perfectly civil, the noncustodial parent may find that he or she has to book a hotel room for the weekend, essentially taking the kids on an extended sleepover once a month. This can be exciting for the children, but it also strips any sense of normalcy and permanency from the noncustodial parent’s visits. If the custodial parent can tolerate sharing the family home with the visiting parent for a single weekend once a month, the kids benefit by enjoying the company of the visiting parent in familiar surroundings. This can be particularly important for very young children.

When the children are old enough to spend extended amounts of time away from the custodial parent, summer vacation becomes a golden opportunity for the noncustodial parent. Visits of several consecutive weeks can be arranged, allowing ample time for parent-child bonding. In addition, on occasion the children may enjoy the adventure of flying out to see the noncustodial parent for a long weekend.

Being a long-distance parent, while always challenging, has been aided greatly by technological innovation over the last two decades. Webcams and services such as Skype that offer video conferencing over the Internet can be hugely valuable to parents who need to stay in touch over great distances. Children often have a hard time with the telephone—particularly toddlers and pre-Ks. A voice alone simply isn’t enough to entertain most children for an extended period of time. They simply need more stimulation. Cue the webcam.

Services such as Zoom or Facetime are such powerful tools for long-distance parents that some judges have ordered that the custodial parent make such tools available to the non-custodial parent. Reading bedtime stories, watching the children play or dance, expressing your delight when they show you a new treasure: these are all priceless interactions that were previously out of reach. The lesson here: if you are an out-of-town parent, take advantage of every opportunity to interact with your children in this manner.

Because Internet video calls take some effort to arrange, parents should consider adopting a regular schedule for connecting with the kids. This has the added benefit of getting the children accustomed to regular interactions over the computer. Instead of complaining that they want to be outside playing or watching their favorite show, the kids will know that the time is always reserved for their out-of-town parent. As with everything else in an effective custodial relationship, communication and cooperation are critical.

Healthcare

Once you’ve determined where your children will live, you should consider how the location will impact their access to healthcare. For parents who live in the same town, the simplest solution is often to keep the same healthcare provider that the children used before the divorce. However, if one parent lives far enough away that visiting the children’s physician becomes a hassle, alternate healthcare arrangements need to be made. With portable insurance, such as Anthem Blue Cross, simply finding the child a new primary care physician in the move-away parent’s new hometown is an easy option. However, when one spouse receives employer-subsidized medical care through an HMO tied to a geographic area (such as Kaiser Permanente), arranging coverage for the children can be trickier. Some HMOs allow members to arrange for medical services for their children with other providers while they are outside of a specified geographic area, but this isn’t always the case. On occasion, buying a portable policy for the children that can be used where both parents live is the best option available.

In addition to thinking about how medical coverage will be handled, you need to decide who will have the authority to handle certain medical matters, such as immunizations. Routine care typically doesn’t require the consent of the other parent, but immunizations require coordination to avoid duplication. Most parents opt to require the consent of the other spouse before non-emergency surgery or hospitalization. Likewise, in all cases parents need to coordinate carefully when it comes to agreeing to and administering the children’s medications.

Education

Although most parents agree that they want their children to enjoy a “good” education, many parents have strikingly divergent views about what exactly “good” means. To some, if means attending the same parochial school they attended as children. To others, it means doing whatever is necessary to get their children into a particular magnet school. For others still, it means doing all the heavy lifting themselves and home schooling their children. As with every aspect of a divorce, clear communication regarding desires and concerns is the key to coming to a workable compromise. Several factors should be analyzed before you decide how to educate children after divorce:

- What can you afford? Many divorcing couples whose children attend expensive private schools are deeply disappointed to discover that paying tens of thousands of dollars a year in private school tuition is no longer a viable option following divorce. Remember, each dollar after a divorce has to be stretched further, as each parent has to maintain a separate household. In many cases, something has to give. If it comes down to an annual extravagant vacation or private tuition, the choice is an easy one. However, some parents are already operating on a budget that allows for nothing more than necessities, and the luxury of private school simply isn’t realistic any longer. To make a sensible decision about what you can afford, do some detailed budgeting and be honest with yourself. “I’ll figure out how to make it work” may be a commendable notion, but amassing large amounts of debt to send your children to private primary or secondary school is rarely sensible. If you are going to sink yourself into debt for your children, focus on college expenses instead. Although this can be extremely difficult to arrange, some enterprising parents manage to obtain scholarships for their children—the best possible outcome.

- Where will they get the best education? This is a highly subjective question, but one that some parents strangely fail to consider. Simply because they attended a private school decades ago, they assume that no better education exists. Do your research. If you have been sending your children to private school, you may be surprised to learn that the public high schools actually offer more honors and advanced placement courses than the local private school. In addition, you may have underestimated the resources available at public schools to deal with your children’s individual needs.

- What do your children want? Of course, the heartbreaking reality may be that your children have been in private school for ten years, and the thought of leaving their friends behind and starting over at a public school is terrifying. In that case, you will undoubtedly do everything in your power to ensure that your children are able to finish secondary school with their core group of friends. On the other hand, some parents never ask their children what they want. They assume that they have to send their children to an expensive private school when the other kids in the neighborhood are all destined for the public school system. In that case the parents can expect that given a choice, their children will opt for public school.

- Which school best reflects your core values? This question is particularly applicable to parents with strong religious convictions. When both parents share the same faith and desires, sending the children to a religious school may be an easy choice. However, many divorced parents consist of a religious spouse and a non-religious spouse. This can create quite a bit of conflict when it comes to education. For instance, one parent may feel strongly that parochial school is the only reasonable choice for the children, while the other parent may feel that the public school system offers a broader and more competitive education.

If you and your spouse disagree about whether your children should attend a religious school, try hard to understand exactly why your spouse feels the way that he or she does. Does his or her position stem from the fear that you won’t instill any sense of religious tradition in the children? Or perhaps the opposite—that you will use religious education to indoctrinate the children in a worldview that sits in direct conflict with his or her own beliefs? Sometimes a compromise is possible. For instance, a couple that includes one Jewish parent might agree that the children will attend public school, but also agree that the children will all attend as much Hebrew School as necessary to celebrate their Bar or Bat Mitzvahs.

Aside from simply deciding where your children will attend school, a number of other details require your attention. For instance:

- Who will participate in school activities? If you wind up following the advice in this book and resolving your divorce with minimal tension, it is very likely that you and the child’s other parent can both attend school functions. In fact, the joint show of support will be incredibly beneficial to your child’s emotional health. Unfortunately, reality intrudes, and some parents simply don’t want to share the same space with the other parent. In those cases, the parents should try to reach agreement on who will attend school functions that require a chaperone (i.e., trips to a museum) and who will help out in the classroom. The same principle applies to parent-teacher conferences. Figure out who will attend these important conferences now to avoid future conflict.

- Will you reward good grades? Consistent treatment with regard to grades is important, and if you hope to incentivize good grades with a reward system, you need to discuss this with your child’s other parent.

- Music lessons, after-school sports, and other extracurricular activities. For many children, school doesn’t end with the ringing of the bell. Music lessons, sports teams, drama rehearsal—the list goes on. Ideally, you will both be able to attend recitals, games, etc., but if that’s not a possibility, try to come up with a schedule that allows equal participation in these important events. Also, discussing who will pay for lessons and fee-based programs is an important part of the divorce process for parents.

Holidays

For divorced parents, no time of the year is more difficult to manage than the holidays. Both parents typically want the children at their own home during the holidays. Conversely, neither parent wants to spend the holidays alone. To ensure that the children have the opportunity to spend with both parents, one of the following approaches can be used:

- Alternating holidays: This is a common way to ensure that both parents and the children get to enjoy the holidays together at least every two years without interruption. To further soften the absence of the children during the holidays, parents can stagger major holidays such as Thanksgiving and Christmas, for example. One parent can take the children for Thanksgiving, while the other has the children for Christmas. The following year the schedule can be reversed.

- Dividing holidays in half: This has the obvious advantage of ensuring that neither parent misses out on any particular holiday, but it has the serious disadvantage of making the holidays a little chaotic. This arrangement works particularly well if both parents live close to each other.

- Celebrate twice: Put yourself in your children’s shoes. Wouldn’t it be fabulous to celebrate major holidays twice? One parent can celebrate a holiday a week before its actual date, and the other can celebrate on the day itself. This works if one parent doesn’t feel “cheated” by missing out on the real thing, and the travel plans of extended family aren’t interrupted.

Decision Making

Many divorced parents struggle with the process of making decisions that affect their children. Who gets to decide important issues? Both parents jointly? The custodial parent? Another adult? In an ideal world, all parents would be able to reach agreement after carefully considering all available options, weighing each other’s opinions fairly, and analyzing the needs of the children. While this is achievable, creating a little structure around the process of making decisions is often a good idea.

Be specific about who gets to make what type of decision, and when. For instance, like most parents, you may agree that everyday decisions affecting the children’s lives will be made by the parent with whom the children are currently living. However, you may also agree that significant decisions (i.e., anything relating to healthcare or education) must be made by consensus.

In cases where one parent has sole physical custody and the other parent sees the children infrequently, it may make sense for the parent with physical custody to have broad discretion regarding the vast majority of decisions that impact the children’s lives. In high conflict divorces with parents who struggle to come to any type of consensus regarding important decisions that impact the children, appointing a third party to make important decisions may be appropriate. However, that option should be reserved for only the most conflict-ridden parents. Appointing someone else as your child’s guardian has serious consequences that should be discussed in detail with a family law attorney.

Dispute Resolution

Expect to reach an impasse with your children’s other parent at least a few times over the years. It’s inevitable. It may be something as seemingly innocuous as whether your children can attend the school trip to Washington D.C., or it may be as serious as whether or not a certain surgical procedure is appropriate. Regardless of the severity of the issue that is the subject of disagreement, you should agree on the approach you will take when the two of you just can’t settle on a decision. The following are some of the standard approaches that parents use to settle disagreements. Consider each approach and think about how it might work given the dynamic between you and your children’s other parent.

- Mediation: While mediation is addressed at length elsewhere in this book, it’s worth mentioning again. Using a mediator is an excellent way to ensure that you are communicating clearly with the other parent while retaining complete control over the proceedings. You don’t run the risk of putting important decisions in the hands of a third party, but you reap the benefit of professional guidance and support.

- Consulting a Counselor or Therapist: Sometimes simply obtaining the input of someone who is trained to diffuse tension, foster communication and facilitate cooperation is all that is needed to resolve conflict. Perhaps you simply can’t understand why your children’s other parent has taken such a hard line on a particular issue. A therapist may be able to coax an explanation from him or her. Understanding the underlying source of conflict often results in resolution. Quite often parents aren’t really certain why they are arguing. It may not be the issue that is being argued about that is the problem, but a longstanding grievance that was never addressed. Therapists are quite skilled at uncovering sources of tension that make cooperation difficult.

- Granting Authority to the Primary Caretaker: As noted above, sometimes it simply makes sense to grant the primary caretaker the authority to make decisions when both parents can’t agree. Certainly if one parent sees the children infrequently, his or her opinion should still be respected, but many parents agree that decision-making authority comes with the huge responsibility of being the children’s primary caretaker.

- Starting Slowly: If two parents are having a particularly hard time agreeing on issues involving the children, it often makes sense to table large items for several months (if possible) while working on communication skills. By starting with basic questions, such as who will attend the children’s recital, you may be able to rebuild enough trust to address larger issues. If needed, take baby steps.

Moving Away

Nothing scares a parent more than the thought of watching helplessly as their children are moved away. The legal framework surrounding “move away” situations is explored in detail in the next section. The practical issues surrounding parental moves are many, and deserve some discussion. Consider the impact that a move may have on the children:

- Less time with one parent: If a parent with majority physical custody moves away and the other parent doesn’t follow, it is likely that the children will see the other parent much less frequently. This is a huge source of stress for children who are bonded with the parent who isn’t moving. Certain technological resources (i.e., online video chats) can lessen the shock, but they are no substitute for physical contact.

- Loss or interruption of friendships: For children who have lived most of their lives in the same neighborhood, a move can be socially devastating. Friends who have been around for years are suddenly out of reach, and the children will have to work hard to make new friends in an unfamiliar neighborhood. This can be difficult when the kids in a new neighborhood have already developed exclusive cliques.

- Adjusting to a new school: Each school has its own distinct feel, and relocating to a new one can truly rattle children. This is particularly true if children are forced to move mid-year. Teachers move at different paces, and being thrust into a new classroom is intimidating at best, and crippling at worst. Children may end up overwhelmed by the academic pace at the new school, or bored and restless and eager for distraction. Either way, adjustment is a challenge.

Moving the children is a surefire way to generate conflict. Avoiding a move during the already unsettling divorce process is ideal, but unfortunately it isn’t always possible. Sometimes a parent must relocate because of a job. Or perhaps a parent who is overwhelmed may want to relocate to be closer to his or her own parents. Regardless of the reason, both parents need to think through the consequences of moving. In many cases, child support will need to be recalculated. In what feels like a stinging wound to the parent who stays behind, not only will child support payments increase (because the parent who stays behind will have the children less frequently), but he or she will also have to travel to see the kids.

If you are considering moving, show your children’s other parent the respect of giving him or her as much notice as possible. Whatever you do, don’t move without warning the other parent beforehand. It could jeopardize your custody of the children. Moving away from the area where the children have been living always presents a number of obstacles. Do everything you can to facilitate the transition, starting with clear and honest communication.

Information Exchange

Scheduling visits and arranging drop-offs are only a small element of a successful co-parenting relationship. It is critical for parents to keep adult affairs out of the communication loop with the children. For instance, a spouse who still harbors deep resentment over past infidelity must be certain this resentment doesn’t infect communications with the children. Your kids should never be conduits for your personal motives. Don’t use your kids to “spy” on the other parent, and certainly don’t use them as messengers. If you want to know if your significant other is seeing someone else, ask him or her. Nothing puts children in a more awkward position than being forced to take sides and provide “intelligence” on the life of the other parent.

Never put a child in the position of asking for a child support payment, or for help with a medical bill. It is incredibly demoralizing for the child. Delivering a message to the other parent that the child knows is based on an unwelcome “adult” topic is awful. Child support is an adult issue. Parents must find a way to communicate about such issues without involving the kids. Failure to do so can be devastating for children for years to come. Divorcing can be unsettling and isolating, and depending on the age of your kids, you may be tempted to use them as a sounding board regarding family finances. Teaching kids financial responsibility at a young age is a great concept. Just don’t let this notion cross over into discussions about support payments.

Some parents have an extremely hard time communicating with each other both during the divorce process and for years afterwards. Facing a spouse who may have deeply hurt you is difficult. Couples without children are often able to make a clean break and heal on their own. Those with kids, however, are not so lucky. Communication is critical, and the only matter for consideration is exactly how those information exchanges occur. Many therapists recommend that the parents transform their relationship from a deeply personal one to a business relationship. For some parents, this is easier said than done.

If you feel queasy at the thought of communicating with your child’s other parent, you need to master the art of concise, business-like information exchanges. What exactly do you need to know? What do you need to communicate with the other parent? Think about this ahead of time. What homework still needs to be done? How are your children progressing with extra-curricular activities? Are there any disciplinary issues that need to be addressed? What are the kids doing for fun? Do you need to discuss any changes to the ground rules (see below)?

If you can’t bear the thought of communicating in person with your child’s other parent, consider exchanging information over the phone. If that is too hard, try email (or if you absolutely must) text messaging. In some instances, an uncooperative pair of parents needs to establish separate relationships with key individuals in the children’s lives, such as doctors, teachers, nannies and event coordinators. Many such individuals don’t want to communicate separately with each parent. Indeed, it creates quite a bit of extra work for them, so it is easy to understand their frustration. Nevertheless, until things calm down enough that jointly communicating with these individuals is possible, be firm in insisting on the necessity of separate meetings and information exchanges.

Consistency and Ground Rules

Children are remarkably adaptable. As a result, they are able to accommodate a certain degree of disparity when it comes to living in each parent’s home. That said, when one parent is extremely heavy-handed with discipline, rules, and order, and the other parent subscribes to a less rigorous lifestyle for the kids, challenges can arise. It is hard enough for many married couples to settle on a set of rules with regard to raising their children together. Add divorce to the mix, and it becomes truly challenging.

The first step to achieving some minimum degree of consistency between two households is to establish an open flow of information. Highlight any behavioral issues you have noticed with your children and discuss how you would like to address them. To establish a better relationship with the children’s other parent and minimize conflict, acknowledge your different parenting styles.

The next step to achieving a degree of consistency is to set a few ground rules. There is almost no chance that you and the children’s other parent will agree on everything. Regardless of the particulars, parents who employ greatly differing parenting styles need to work together to establish some basic ground rules for their shared custodial relationship. For example, decide that no matter whose house the children are living in, they won’t watch more than one hour of television a day. Or perhaps you can establish a ground rule based on consumption of fast food—not more than once a week.

Imagine the following scenario, and you will immediately grasp the problems that accompany the combination of vastly differing parenting styles and no ground rules:

Jan and Jeff have two children, Steve, aged 12, and Alice, aged 6. Jan is a very permissive parent. She thinks the kids should be able to dress however they like, listen to whatever strikes their fancy, and watch any sort of movie or play virtually any type of computer game. So long as the kids are in bed by midnight, she is also not particularly worried about their schedules. She thinks Steve should find the motivation for homework “from within” and she only wants Alice to learn a musical instrument “if she wants to.” She does encourage Steve to continue pursuing his love of the electric guitar by taking him to lessons. Lastly, she has no problem with allowing the kids to subsist on a diet that largely consists of fast food and pizza.

Jeff is a very different type of parent altogether. When the kids spend the week at his house, they eat three healthy meals a day, are firmly tucked in bed by 8:30 pm (Alice) and 10:00 pm (Steve), watch no television, and study classical music with their father. Jeff refuses to support Steve’s electric guitar lessons, insisting that if he wants to learn to play the guitar, he should start with classical guitar. While to many grownups Jeff seems like a good but somewhat severe parent, imagine how Steve and Alice feel about his parenting style. Able to run wild in Jan’s home, Steve and Alice have naturally dubbed their father the “no fun” parent. Worse still, it takes the kids at least two days to resettle after the madness of living in Jan’s house before they can transition into the lifestyle that prevails at Jeff’s house. In short, the kids are continually off-balance because of their two drastically different lifestyles, and Jeff is constantly faced with the grumbling and unpleasant attitudes that result from his status as the less permissive parent.

As you might imagine, Jeff and Jan don’t communicate well. They enjoy very different lifestyles, and their children pay the price for their unwillingness to lay down some fundamental “ground rules.” Though it may seem that Jan should simply try to adhere to Jeff’s more stringent parenting rules, this isn’t necessarily the case. If Jan is going to impose any sort of discipline in the children’s lives, it will only be if Jeff is willing to make a concession or two and loosen up a little. Jeff might consider an occasional trip to the pizza parlor, or perhaps letting the kids stay up late on an odd Friday night. And while Jeff detests television, he may consider letting the kids watch a few educational programs.

In the end, simply by conceding the electric guitar lessons, a slightly later bedtime, and loosening up on television, Jeff is able to get Jan to agree to the following ground rules:

- No more than four fast-food meals a week

- Homework will be done every night

- Piano lessons for Alice once a week, whether she likes it or not

- Electric guitar lessons for Jeff once a week

- No more than two hours of television a day

- Weekday bedtimes of 9:00 pm (Alice) and 10:30 pm (Steve)

The overriding purpose of ground rules is consistency. Leading two very different lifestyles is difficult for children. Remember, the ground rules are not only for your sanity, but also for your kids’ well-being. You both want your children to do well. Laying down consistent rules will not only enable them to perform better in school and other activities, but it will also prevent one parent from being put in the unfair position of being the sole disciplinarian. Some topics for consideration as ground rules:

- Sleep schedules (i.e., when is bedtime?)

- Disciplinary styles (“time-outs” vs. “extra chores” etc.)

- Music lessons and sports (mandatory vs. discretionary)

- Allowance (i.e., how much?)

- Policies on driving (for teenagers over 16)

- Sleepovers with friends (permitted, and if so, how often?)

- Television watching (what shows and how often?)

- Computer games (what type and when can they be played?)

- Diet and nutrition (types of foods, permissible splurges)

- Religious education (what type and how much?)

Other Issues to Consider

Hired Help – Nannies and Other Caretakers

Though the term is a bit outdated, please note that in this discussion the term “nanny” is simply meant to refer to a caretaker for the children, whether male or female. If you are fortunate enough to have the financial resources available to hire a nanny in lieu of other arrangements (such as daycare), you may find that your nanny provides a welcome dose of stability to the lives of your children. Indeed, when everything else seems to be coming apart, kids subject to joint-physical custody will be greatly relieved to know that the nanny will travel with them between homes.

Don’t surprise your nanny with the news of divorce at the last minute. Let him or her know that you are contemplating separation, and that your children may soon be splitting time between two households. Also try to get a sense of whether he or she plans to stick around for the next year or so, and if your kids have already bonded with the nanny over a period of months or years, encourage him or her to stick it out, at least for the time being. Let your nanny know that the divorce process will be highly unsettling for your children, and that he or she provides an invaluable sense of stability. If needed, you might even consider offering your nanny a raise to ensure his or her continued service.

Ideally, you and your spouse will sit down with the nanny together and explain your new custody arrangement. Explain that the fundamental ground rules that the nanny has been operating under haven’t changed, but that he or she will be expected to travel back and forth between two homes. You should also address compensation (who will be responsible for paying the nanny, and when). Lastly, without asking your nanny to divulge information provided to him or her in confidence by the children, do ask for regular updates regarding the nanny’s sense of the children’s well being. Divorce can make children act out, and in many cases a nanny will witness the most severe manifestations of this phenomenon. Your nanny will be of invaluable service when it comes to assessing the need for therapy or a simple “heart-to-heart” with your children.

The New Partner

Nothing can be more traumatic for a divorced parent than being introduced to the other parent’s new partner. Entire books have been written about the art of step parenting and the art of interacting with stepparents. First, chant the mantra over and over again in your head, “I will act like a grownup for the sake of my children.” It is incredibly common (and very destructive) for one parent to demonize the other parent’s new partner or spouse. Of course, this is particularly true when the new spouse was embroiled in an affair with the parent prior to divorce. Anger and resentment are natural, and in many cases, simply inevitable. If you find yourself seething over the very existence of the “home-wrecking” lover who is now the other parent’s new spouse, you are not alone. Talk it out in therapy, shout your frustrations into the wind, or otherwise deal with your anger and disappointment. Do not drag your children into your emotional minefield.

In some cases, one parent may actually take a liking to the other parent’s new spouse. This is becoming more common as the stigma surrounding divorce and remarriage fades, and spouses increasingly turn to conflict resolution (e.g., mediation) to resolve disagreements during the divorce process. If you are lucky enough to find yourself charmed by the new addition to the family, the process of integrating the kids’ new stepparent into the custody routine is fairly simple. You likely won’t mind if the stepparent attends important events in your children’s lives (recitals, graduations, etc.), and you won’t flinch if the stepparent is the sole caretaker of your children for periods of time (for instance, if the children’s other parent travels frequently for work).

In other cases, one parent simply can’t stand the other parent’s new partner. This can obviously make interaction between the two tense at best, and can make discussions regarding the role of the new stepparent very difficult. If you find yourself livid at the very thought of the new stepparent interacting with your children, you have your work cut out for you. Remember, you can’t tell your children’s other parent whom to choose as a partner. It’s simply not your decision. Sooner or later, you will have to learn to cope as best you can. While it may be wise to avoid face-to-face interactions with the new stepparent, be prepared to encounter him or her on the phone on occasion despite the most diligent avoidance strategy.

Regardless of whether you are pleased with the other parent’s choice of a partner or not, you will have to address certain issues. Some basic items for discussion include the following:

- What will the children call the stepparent? This is a very sensitive topic for many parents. Fear of being displaced is a very powerful emotion, and the possibility that the children will call this new stepparent “dad” or “mom” is extremely threatening. Therapists profess differing opinions when it comes to the appropriateness of calling a stepparent “mom” or “dad.” Some believe it is patently unfair to the true parent, while others state that using those terms is simply natural for children in some custodial situations. As always, coming to a clear understanding with the children’s other parent is critical. Having your children continually refer to their stepparent as “mom” or “dad” can be devastating when this was never discussed beforehand. If either you or your spouse are particularly sensitive about the possibility of having your children call someone else “mom” or “dad,” you should both strongly consider honoring the other’s feelings. Come up with another name. In many cases, simply having the children refer to the stepparent by his or her first name is appropriate. If this doesn’t feel right, get creative. Just do something that allows the concerned parent to hang on to his or her treasured title.

- How will the stepparent handle discipline? Nothing is a surer recipe for an extensive custody dispute than the children’s insistence that the stepparent is engaging in unduly severe discipline. No parent wants to think of any adult treating his or her children harshly. Indeed, even teachers are often censured for the most rudimentary discipline. Imagine the emotional response when a parent discovers that a detested stepparent spanked one of the kids. It gets ugly. Avoid this scenario by discussing discipline ahead of time. Before insisting that the new stepparent play no role in disciplining your child, think about how this might be damaging. Indeed, making the stepparent a “toothless” adult figure in the children’s lives rarely does anyone any good. If the stepparent can’t govern through discipline, he or she may be forced to provide inducements for good behavior. This can lead to very spoiled children. Imagine if providing a chocolate chip cookie was the only way to get your children to behave? It would be disastrous, wouldn’t it? Discuss discipline with the child’s other parent. Try to agree upon appropriate methods of discipline that can be used by the stepparent (time-outs, restricting access to favorite activities, etc.). Above all, be clear. If you are spooked about the thought of anyone else disciplining your child, express your concerns to the children’s other parent as gently as you can. You may be surprised by his or her ability to reassure you.